by mantunes

In Newark, small events, almost comically unimportant in the short term, are a pinhole through which you can see a wider kaleidoscope of poor government decisions, larger societal failures, and the banal tragedy that has come to represent how local policy is made. When I wrote “The Tragedy of Newark’s Commons” in 2022, I believed that Newark had peaked in its enclosure of open spaces. I had no illusions that the piece would become a rallying cry to city officials and residents. (Our readership, though strong, is nowhere near that numerous or influential, yet.) Still, I had a sense, given the mayor’s open call for more green space and the expanding economic base of the city’s residents, that we would rethink how we treat public resources. Strolling past the black slats surrounding one of those formerly open spaces right outside Penn Station, I came to a stark realization. I was profoundly mistaken.

The recent fencing around Peter Francisco Park is baffling.1 If you are not familiar with the park—even most native Newarkers are unlikely to know which park I am referring to—it is a one-acre green expanse right outside Penn Station’s eastern entrance, flanked by Ferry Street, Edison Place, and Raymond Plaza East. If you’ve been to the Ironbound, you’ve almost certainly walked by it, if not through it. Named after an Azorean-Portuguese immigrant who fought in the American Revolution (the so-called “Hercules of the American Revolution”) as part of the Bicentennial celebrations of 1976, the park goes as far back as 1966. It’s also home to several moments: a World War II war dead stele [1974]; an obelisk celebrating the Bicentennial and Peter Francisco [1976]; a memorial to the Portuguese-Americans who served in Vietnam [2018]; and a monument to the immigrants of Newark and the East Ward in particular [2018]. The park, despite its location and prominence, is not listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Aside from its monuments and memorials, the park may be most known for its visible population of unhoused individuals and families. So persistent was their presence that many locals associated the park with them. Downtown Newark is replete with public spaces where unhoused individuals congregate and local residents and business owners will complain about their presence. Peter Francisco Park is far from unique when it comes to the presence of the usual set of urban ills.

Things, however, seemed to have come to a head in 2021 when the administration stated that it would begin to require volunteer food distributors to get a food handler’s permit from the city. This upset many from homeless relief organizations and progressive groups to well-meaning residents and even saw coverage in the New York Times. The backlash was so strong that Mayor Baraka had to do some damage control, explaining that this was about the safety of the unhoused individuals receiving the food and not about clearing the park of them. After the initial hub bub, the issue faded into the background.

The issue of what to do with Peter Francisco Park went into stasis until the beginning of June this year. Right after Portugal Day weekend—the most highly trafficked weekend for that park—a permanent black metal fence surrounded the park with one means of ingress and egress —a gate on the far left side of the southern edge of the park. The fence went up very quickly, in a matter of days, and seemingly without any notice to the community or the residents of the city at large.

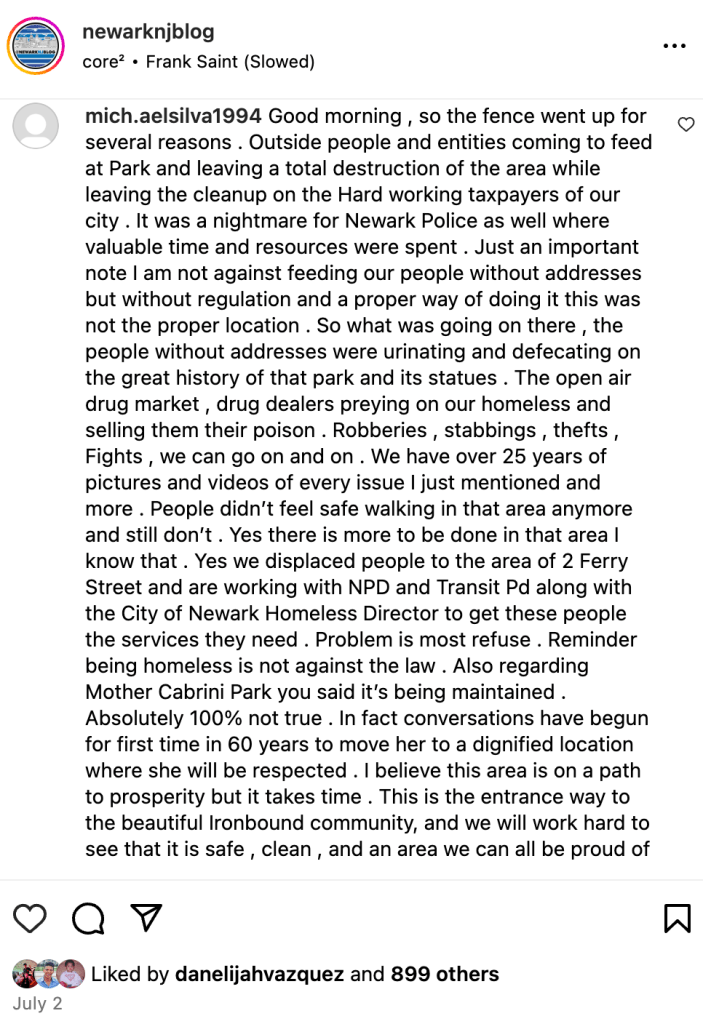

The reaction on social media and community forums evinced a mixture of shock, outrage, and confusion. Perhaps the most popular and discussed post came from the Instagram account @newarknjblog, which has over 25,000 followers.2 The post consisted of a drone shot over the park that fully encompasses the fencing around the park and had over 890 likes and over 240 comments and replies at the end of July. The comments were largely critical and included descriptors like “fucking despicable,” “not cool,” and “completely fucking stupid.” Most notably, there was a comment from @mich.aelsilva1994 saying that the park was a “nightmare” for Newark police, functioned as an “open air drug market,” and that “people didn’t feel safe.”

Because of the definitiveness of the Instagram post, I decided to reach out to the actual Councilman Michael Silva on behalf of the Newarker Magazine to find out his official view on the matter, especially if the comment did not best or fully express his view.3 Initially, I had sent him six questions and allowed for a written response to those questions.4 Instead, his office responded with a request for an in-person meeting to discuss the issue, which (to be honest) I hesitantly accepted.

Council members’ offices are much smaller than you would think. Not more than ten feet separated the walls in the room, and the Councilman and I had no more than three feet between us. The intimacy both disarmed me and heightened the disparity in the power relationship. I, a wannabe writer about this town, and he, an elected representative of a 60,000 person constituency. For around 30 minutes, Councilman Silva entertained several questions I had with the usual feigned sincerity that comes from an elected official in this city.

“[It] wasn’t that type of park.” He started. It is really a “park for monuments.”

Councilman Silva explained that he had been a detective with the Newark Police Department in the Ironound from the 2000s to the 2010s—by his estimation, an 18-year period. While the park has always had its issues, he said that it was only in the last few years that he began to receive complaints about the unhoused individuals using the park. This problem devolved as groups, for the most part religiously affiliated, began to distribute food around the edge of the park. Silva said that these individuals—“outsiders” as he stated—would leave the containers and the remains of what they had not eaten in the park and that it fell on the city to clean up after this mess. On top of that, urinating and defecating in the park became a regular occurrence, and there were even some stabbings, according to Silva. As time drew on, the problem got “progressively worse.”

Silva stressed that he supported the homeless and wanted the city to provide the services they need. From Silva’s perspective, this was a problem he inherited when he was elected to the Council in 2022, after a tightly contested four-way race and run-off. The issue of what to do with the park was front and center in the race. He explained that business owners, as he was on the campaign trail, would complain to him about the issues going on in the park. They told him that they were losing customers, who they said felt unsafe around the park. Upon election, Silva said he worked with the city administration to use “code enforcement” to both help inform the unhoused individuals where they could receive food and to stop groups from distributing food around the park.

I pushed Silva on the decision to put a fence around the park and the procedures around approving and implementing the enclosure. What I learned surprised me. Silva explained that the city council, by resolution,5 “leased”6 the park to the Ironbound Business Improvement District (IBID), a municipally-created organization with the power to collect fees from business owners on and around Ferry Street and tasked with keeping the area tidy and promoting the businesses there. The IBID would both take over maintenance of the park and run events within the park. They also oversaw the placing of the fence, which Silva explained was paid for both by the city and by the IBID. I was slightly taken aback because I had been following what had been going on with the park—specifically, over the last two months, and generally, over the last decade—and I have never heard there were even plans to work with the IBID. The IBID has issued no press releases or communications about its take over the park.

Silva further related that the park would remain accessible to residents and outside groups but that they would have to request a permit to gain entry and to use the park.7 I asked him what the procedure was for obtaining such a permit. He said that people who were interested could reach out to his office to obtain the permit. I asked if I, as a resident, would be able to access the park just to see the monuments, and he reiterated that I would need a permit. However, Silva emphasized that he and the IBID had plans to hold events in the park, such as a “flea market” and would not allow the park to fall into disuse.

With the interview nearing its end, I only became more confused. For example, if the city has been enforcing the regulation around food distribution in the park, what was the need for the fence? I pressed the question to Councilman Silva, and he responded that the feeding issue had abated but that he and the city remained concerned about the other issues, including the urinating and the defecating in the park and that the fence was a necessary component in addressing this.

I also commented that the increased policing in front of the convenience store at the intersection of Ferry and Market Streets seems to have abated the issue of loitering and congregating around that corner and could perhaps be extended to the park across the street. Silva went into an digression about the creation of a new precinct, hinting that a police substation might go into the former 7-Eleven, and how this would help alleviate policing in the East Ward overall—points that I found hard to follow.

Silva wrapped up by saying that he did not want to resort to putting up the fence but that “something had to be done.” He felt that the park was not being used for “families” and that he wanted to make the park a focal point for activities such as the above-mentioned “flea market.” He declared, “So long as I am Councilman, that fence is staying up.”

I walked out of City Hall with many questions still unaddressed. For such a visible park, why were there no communications or meetings in the lead up to the fencing? How could the park, a recipient of the State of New Jersey’s Green Acres Fund and listed on the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s Recreation and Open Space Inventory, be permanently closed off to the general public? Why wasn’t the park handed over to the Newark City Parks Foundation, as five other parks had been? How could people, with a genuine interest in seeing the statues or paying their respects, enter the park without having to go through a cumbersome process of obtaining a permit? Was the fencing really the best way to address the residents’ concerns over safety and cleanliness in the area?

Despite the outcry on social media, two articles in major publications, and a consensus from people I have talked to, I doubt there will be any marches to save the park. It’s unlikely that an advocacy group will launch a lawsuit against the city and the IBID to get the park reopened. The vast majority of Newarkers will walk past the park, shrug their shoulders, and move on with their lives.

Councilman Silva has an unenviable task. The current housing crisis is a national problem, and Penn Station is a natural congregation point for anyone to buy some time as they seek help or just need to hide where there is sufficient presence from commuters and other residents that they can feel relatively safe. Silva has to balance those needs with the desires of residents and business owners (and “outsiders”) to see the park “cleaned up.” Individual members of the City Council, while holding immense political influence, are frankly powerless when presented with these kinds of societal problems.

This balancing is not easy, and these issues are fundamentally structural and long-term, not prone to quick solutions. Newark is also a city where the political culture runs on the press release and the Facebook post. A photo opportunity is just as, or even more, important than the piece of legislation or the program being implemented. I have termed this approach as “all sizzle, and no steak” approach.

This approach to local policy is the driving force behind the implementation of the fence. The fence is not a surgical fix to the problem, one where the defecation, urination, and stabbings are kept to a minimum but where everyone has access to the park. The fence instead is a visible and constant symbol that Councilman Silva and the city are doing something about the problem. This is why he was so definitive in his defense of the fence. It is a message to the East Ward that your local representative is listening and doing something to fix your problem right now. I am not against short term fixes, but as the old saying goes, nothing is more permanent than a temporary solution. Silva is likely right that this fence will be around for a very long time, if not forever. What we have lost, however, is another public space. Heather McGee, in her seminal 2021 book The Sum of Us, highlights the problems when we deny a public resource or a benefit because of our feelings about a particular group. Though focused on the history of racism in this country, the book offers a profound insight on what happens when we level down as a society. When we fence off a park, we are not only denying free access to the unhoused; we are also denying access to a public benefit to all of us. By addressing one narrow problem, we have made everyone worse off.

mantunes is a resident of Newark who writes about the city (and uses its parks with some frequency).

- I would like to thank Matt Kadosh and Steve Strusnky for their reporting on the fencing around the park. Although I started my research and investigation before the publication of their articles, I found what they wrote to be illuminating and helpful in filling in some of the gaps. ↩︎

- For full disclosure, I am personal acquaintances with the manager of this instagram account and consider them a friend. ↩︎

- That is, if the comment is actually from an account he controls. In my interview with Councilman Silva, I neglected to ask if he wrote the comment. In the end, I decided that the comment is more illustrative of the general tenor of the debate around the park and not a revelation of Silva’s official stance on the park. ↩︎

- The questions were:

1. What are the reasons for the fencing around Peter Francisco Park?

2. One of the stated reasons for the fencing is an issue with the feeding of homeless people in and around the park. Does fencing effectively address this issue?

3. What procedures were followed for putting up the fencing? For example, were other state and city agencies consulted?

4. Peter Francisco Park is listed on the Recreation and Open Space Inventory on the New Jersey Green Acres program website. Is the fencing in compliance with the rules governing such spaces?

5. How does fencing comport with the Mayor, the administration, and the council’s stated priority of making parks and recreational facilities accessible to the Newark community?

6. Were alternatives to fencing explored?

↩︎ - A search for “Peter Francisco” and “Ironbound” on the city council’s official legislation and council business website over the last four years resulted in no relevant resolutions or ordinances. ↩︎

- After my interview with Silva, it became clear that he misspoke when he said the city had “leased” the park to the IBID. The IBID, instead, has a memorandum of understanding with the city to maintain the park and not an ownership/real estate interest in the park. I was upfront with Silva and his staff about my journalistic intentions regarding the piece. The slippage of the language, in my estimation, reveals either how the Councilman was blindsided by the reaction and not prepared for the detailed questions I was going to ask or that the issue around the park was just not a priority for him. ↩︎

- The city’s official website does not have an explanation of how to obtain a permit for entry to the park. A source on background said that the City Clerk told them that they could reach out to the Parks Foundation, who as an official matter does not have a purview over Peter Francisco Park, and that they would process the permit.

↩︎